Be yourself; Everyone else is already taken.

— Oscar Wilde.

This is the first post on my new blog. I’m just getting this new blog going, so stay tuned for more. Subscribe below to get notified when I post new updates.

Be yourself; Everyone else is already taken.

— Oscar Wilde.

This is the first post on my new blog. I’m just getting this new blog going, so stay tuned for more. Subscribe below to get notified when I post new updates.

Narrative is hard. Being in post production myself, I avoid the stress of creating a succession of events that gets the audience emotionally invested. But the recognition and results of a good narrative is rewarding for creator and consumer alike. The Last of Us excels at this. In this journal, I’m going to dive into how The Last of Us tells a powerful narrative through world building and character empathy.

Show don’t tell. That’s rule #1 of good narrative. For video games, the easiest way to show the most in the shortest amount of time is in the game space. In Simon Egenfeldt-Nielsen’s chapter, “Narrative,” he says, “The most important component of a game world is the game space” (175). The Last of Us entertainingly delivers exposition through the world around you. From the start, you’re imbued with the mass panic of the outbreak. You watch the events unfold from a distant explosion to Joel’s fear and then on the streets. Everyone is screaming, sirens ringing, and fires raging. The game sets the tone for what’s to come.

Jump to present day. One of the first things you see is the execution of two civilians. Even worse, it’s done in the middle of the street and treated as the norm. This combined with the the PA system, military, and graffiti are the “fictional clues” Egenfeldt-Nielsen mentions: “These fictional clues certainly stimulate the player’s imagination to turn the playing experience into a kind of narrative-related experience” (173 Egenfeldt-Nielsen). The game is filled with these to engage the player’s imagination and further invest them.

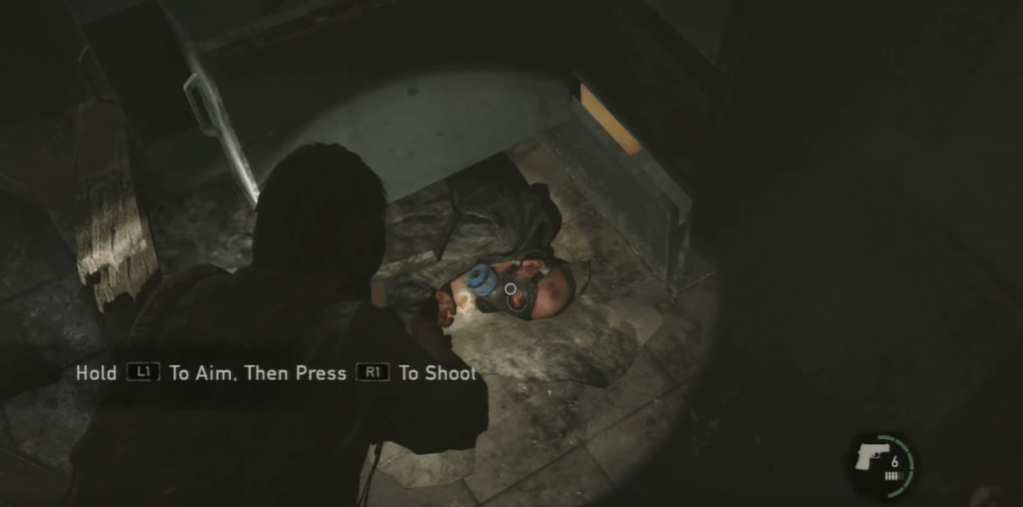

For The Last of Us, since the characters you play as are set (130-131 Shaw), I want to talk about identifying with them. In Adrienne Shaw’s chapter on connecting with characters, she describes this as “identifying with the char.’s situation, experiences, and personality regardless of … shared identifiers” (112 Shaw). The Last of Us tells its stories so well that all you can feel is empathy for their characters. Joel struggles with his daughter’s death, and Ellie with her loneliness. The game tells its story through cutscenes and gameplay alike. After Ellie’s kidnapping, you notice her NPC being less responsive and optimistic. One of my favorite parts of the game is when they teach the shooting mechanic: mercy killing.

The Last of Us delivers a Master Class on video game storytelling. It’s evident in its immersive, grim world and continues through the characters’ experiences and relationships. It’s that attention to detail that makes the game so good.

Works Cited

Egenfeldt-Nielsen, Simon. “8: Narrative.” Understanding Video Games: The Essential Introduction. Routledge, 2013.

Druckman, Neil. The Last of Us. Naughty Dog. 2013.

Shaw, Adrienne. “3: He Could Be a Bunny Rabbit for All I Care!: How We Connect with Characters and Avatars.” Gaming at the Edge: Sexuality and Gender at the Margins of Gamer Culture. University of Minnesota Press, 2015.

For this Play Journal, I want to talk about the successful aesthetics of Assassin’s Creed Syndicate.

AC Syndicate is the 9th installment in the Assassin’s lineup starring a pair of twin assassins in Victoria era London. With that sentence alone, you can predict a lot of aesthetics. I played this game when it originally came out in 2015, but re-playing it through the lens of media studies, I’m able to articulate why I enjoyed it so much in the first place. Simon Niedenthal says that one of the aspects of game aesthetics is “the sensory phenomena the player encounters in the game” (Niedenthal 2). This means “the way a game looks, sounds, and presents itself to the player” (Nidenthal 2). And, being a AAA video game, Syndicate has plenty to offer on those fronts. The graphics and scope are stunning. Here’s a screenshot of the entire map to show how grand the scope is.

Niedenthal also says that mechanics are the verbs of gameplay while the aesthetics are the nouns and adjectives (Niedenthal 5). In Syndicate, the two complement each other so well. For example, the fighting mechanics are nothing new to Assassin’s Creed, but with the new melee weapons and finishers, the combat has been adapted to reflect the brutal street gangs of Victorian England. Furthermore, the free running, carriages, and fast travels provide the option to traverse such a large world much more quickly. Even the grappling hook, albeit some suspension of disbelief required, felt fitting since we’re set in the Industrial Revolution.

On the other hand, you can also take your time and enjoy the amount of detail populating the world from the architecture of Buckingham Palace to the side missions and diverse people on the streets. Each of these options allows the player to be more hands-on and free in their navigation.

Which brings me to another important element of aesthetics: sound. Karen Collins says that “sound works to control or manipulate the player’s emotions, guiding responses to the game” which “creates a different (and in some cases perhaps more immersive) relationship between the player and the character(s)” (Collins 133). All the sounds in Syndicate work to further immerse the player in this world. Playing the game again, I’m noticing more details like the sounds of individual children playing in a courtyard and the variations of footsteps based on the type of surface you land on. Then, there’s the score that has blown my mind since day one. Syndicate was the first game that made me go, “Wow, the music here is amazing.” One of my favorite things to do is climb to the top of Big Ben solely to hear the music swell. Then, the music would change to be timed with your Leap of Faith. Amazing.

Assassin’s Creed Syndicate is a great example of all the small things it takes for effective world building. It’s a blend of the visuals, mechanics, and sounds working together to create an emotional experience for the player.

Works Cited

Collins, Karen. “Chapter 7: Gameplay, Genre, and the Functions of Game Audio.” Game Sound: An Introduction to the History, Theory, and Practice of Video Game Music and Sound Design. MIT Press, 2008, pp. 123–137.

Côté, Marc-Alexis. Assassin’s Creed Syndicate. Ubisoft Quebec. October 23, 2015.

Niedenthal, Simon. “What We Talk About When We Talk About Game Aesthetics.” DiGRA ’09 – Proceedings of the 2009 DiGRA International Conference: Breaking New Ground: Innovation in Games, Play, Practice and Theory, vol. 5, Sept. 2009.

For this Play Journal, I played Limbo, an unapologetically morbid yet entertaining platformer. This game has simple rules but the creativity of the mechanics generates puzzles demanding the player’s reflexes and intellect.

According to Fullerton, rules do three things: “define objects and concepts” (Fullerton 77), “restrict actions” (79), and “determine effects” (79). Limbo plays heavily into rules not having to be “something that players must directly manage” but rather “gain an intuitive knowledge” (78). The only explicit rules are the player’s following:

Besides that, the player has to discover the game-defined objects and concepts. It basically goes like this. The game puts something random in front of you and says, “Figure it out.” The tasks are simple enough that it’s not an impeding learning curve. You quickly discover what’s possible, such as moving boxes and climbing rope. Moving to the game’s restrictions, it’s basic things like being bound by gravity, unable to swim, and being a one-hit kill. The first two parts of Fullerton’s definition are straightforward in Limbo, but the game’s heart lives in how it “[determines] effects” (79).

Since this is such a major part of the game, I want to now integrate the concept of mechanics. Sicart defines mechanics as “methods invoked by agents, designed for interaction with the game state” (Sicart). Since you are only given five keys, the whole game revolves around triggering effects and invoking methods. And the effects are often unexpected. This can all be summed up by Sicart’s term of “contextual mechanics,” that is, “mechanics that are triggered depending on the context” (Sicart). I remember one part where I pulled a lever, and, without warning, the game began to rotate with the gravity changing with it. It made me sit up and quickly figure out what to do. I had to time my jumps, swing on a rope, and avoid circular saws. I, of course, died a lot, but thanks to the game’s rules, its checkpoints are many and short in between. In Limbo, one lever could trigger a rotating world, another could start a rising flood, while a third could activate an electrified floor.

Limbo surprised me at how inventive a game could be with such few keys. An important note from Fullerton is that “rules that trigger effects … create variation in gameplay” (Fullerton 79). And the game did just that. It’s unexpected nature creates unique challenges that keep players interested. The game developers achieved this with the minimal exposition and lack of instruction. I now see that they in fact intended this. Sicart ends his article on the relationship between mechanics and player experience. He says, “these games are intended to create emotional experiences based on the agency of players with the game state and how it reacts to their input” (Sicart). Limbo drops the player in a world bound for discovery and the unexpected.

Works Cited

Fullerton, Tracy. “Rules.” Game Design Workshop: a Playcentric Approach to Creating Innovative Games. CRC Press, 2019, pp. 76–80.

Jensen, Arnt. Limbo. Playdead. 2010.

Sicart, Miguel. “Defining Game Mechanics.” Game Studies, 2008, gamestudies.org/0802/articles/sicart.

For this assignment, Osvaldo “Oz” Jimenez and I went to Arcade UFO. Our game of choice was Mappy, the 1983 Namco game.

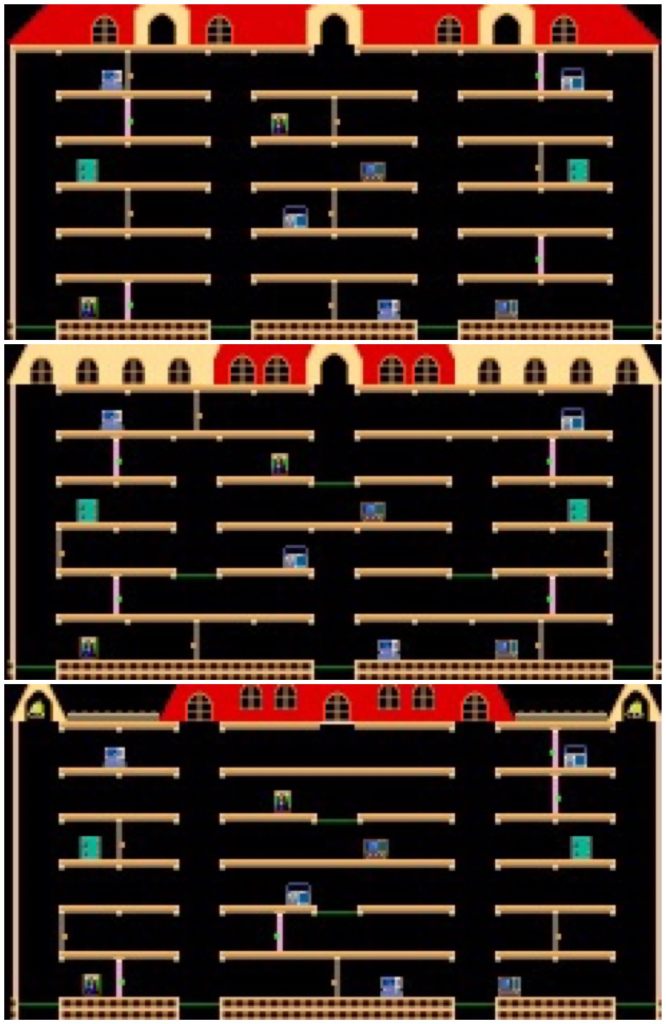

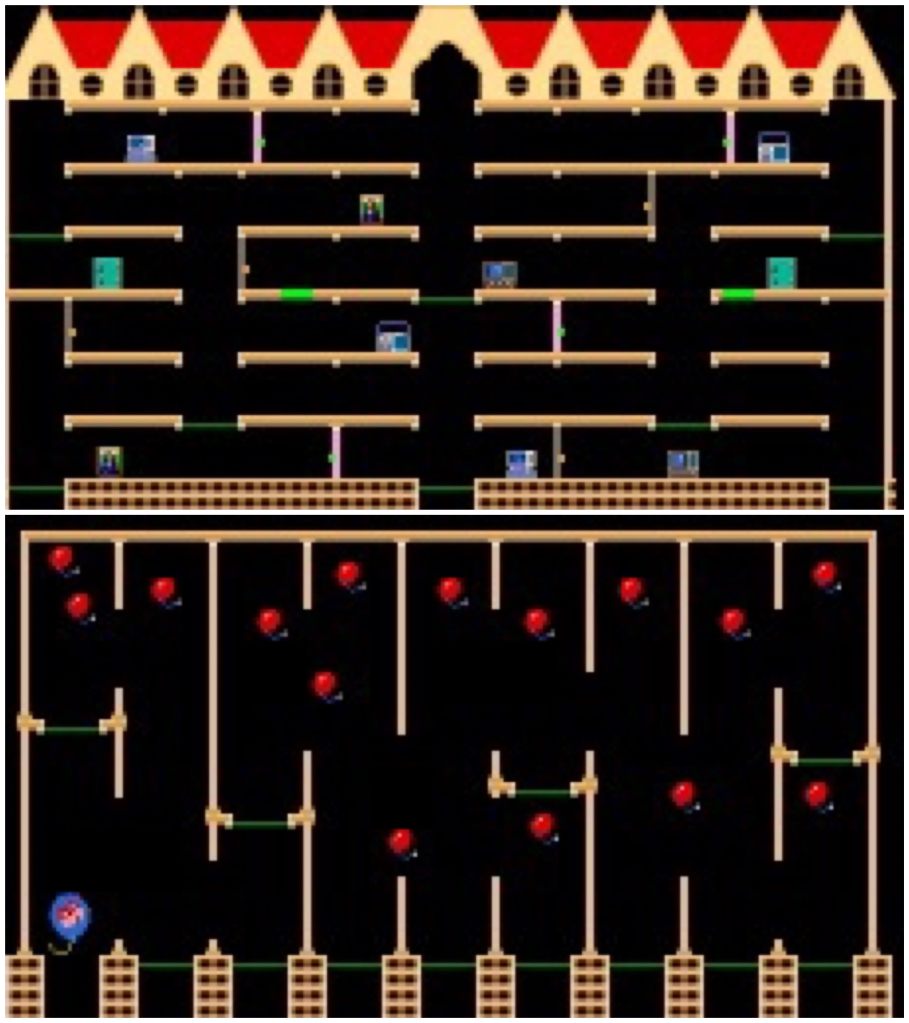

I’ve never heard of this game, but right out the gate I could see elements of the classic arcade that Rouse discussed. It’s a platformer where you play a mouse police and have to collect all the loot while avoiding enemies. You simply move left and right with the joystick and use one button to open doors. To get deeper into the mechanics, you can open doors that knock out the cats and dash you in a specific direction. Special doors would send a one-time, unilateral shockwave knocking out all enemies in its path. There are lines you can lines you can bounce off of in between the platforms so you can reach different platform levels. You lose one of your three lives every time you get touched by an enemy cat. Mappy also allows you to get an extra life every 20,000 points. Already, we’ve touched on Rouse’s traits of simple gameplay and multiple lives. Additionally, Mappy has infinite play with the trope of increasing difficulty. The platforms would be arranged one of four ways and/or there would be more enemies. Then, there’s the matter of scoring. You earn points for specific actions such as jumping on a line, picking up treasure, and varying scores for knocking out enemies with the potential for multipliers via multikills. And then, there were intermittent speedrun levels with the sole goal to boost your score. The game emphasized the competitive nature of high scores by having it at the top of the screen the entire time. And, of course, the classic opportunity at the end to add a three character name to cement yourself in the top 5.

Which brings me to a vital aspect of the game: the interconnectedness. The locations of loot, lines, platforms, and enemies hit the balance of challenge and reward to keep you playing. You have to balance offensive and defensive strategies. The doors can knock out enemies, but they can also send you flying into them thus killing you. A neat rule is that the cats can’t hurt you while you’re falling/jumping on the lines. You could use these for a brief reprieve and decide your next move, but too many consecutive jumps would permanently break the line. But when the cats would be jumping with you, you have to gamble and dash onto a platform and pray a cat doesn’t follow. All of these elements worked together to create escalating tension. Maybe you knock out four cats in one swoop with the special door, so you feel calm. But all of a sudden, a cat charges you from off-screen so you have to quickly escape it by jumping off the platform. These ebbs and flows of tension along with the broader moments of the speedrun levels create a game that retains your attention in an entertaining fashion.

This is an example post, originally published as part of Blogging University. Enroll in one of our ten programs, and start your blog right.

You’re going to publish a post today. Don’t worry about how your blog looks. Don’t worry if you haven’t given it a name yet, or you’re feeling overwhelmed. Just click the “New Post” button, and tell us why you’re here.

Why do this?

The post can be short or long, a personal intro to your life or a bloggy mission statement, a manifesto for the future or a simple outline of your the types of things you hope to publish.

To help you get started, here are a few questions:

You’re not locked into any of this; one of the wonderful things about blogs is how they constantly evolve as we learn, grow, and interact with one another — but it’s good to know where and why you started, and articulating your goals may just give you a few other post ideas.

Can’t think how to get started? Just write the first thing that pops into your head. Anne Lamott, author of a book on writing we love, says that you need to give yourself permission to write a “crappy first draft”. Anne makes a great point — just start writing, and worry about editing it later.

When you’re ready to publish, give your post three to five tags that describe your blog’s focus — writing, photography, fiction, parenting, food, cars, movies, sports, whatever. These tags will help others who care about your topics find you in the Reader. Make sure one of the tags is “zerotohero,” so other new bloggers can find you, too.